Tamil Muslim diaspora, patronage and place-making

The derelict Muslim heritage sites along Chulia Street have aroused my curiosity since the early 1990s… When faced with such enduring evidence, an urban historian can only ask, who were the Chulias? Why were they so important to early George Town? What happened to them? This book is an attempt to answer those questions and to add another layer of historical interpretation to the rich historic urban landscape of the George Town World Heritage Site.

Khoo Salma Nasution, The Chulia in Penang: Patronage and Place-Making around the Kapitan Kling Mosque, 1786–1957

To purchase the book, click

here

Farewell photograph at Kapitan Kling Mosque in Penang in 1924 on the transfer of Encik Ahmad Jalaluddin bin Sheikh Muhammad from Penang Free School to Kuala Kangsar Malay College. Arkib Negara.

About the book

Excerpts from the Introduction

The Kapitan Kling Mosque, better known today by its Malay name, Masjid Kapitan Keling, is a historic centre of Islamic devotion and congregation in George Town, the capital of Penang. With a prominent dome and minaret, this fine monument occupies a notable position in the core zone of the city’s World Heritage Site. To the north is Chulia Street, once thickly settled by Muslims from southern India, and today still full of character and life. To the south is Buckingham Street, modern and regular, alluding to British patronage of the mosque and its community in colonial times. The address of the mosque is Pitt Street, not so long ago renamed ‘Jalan Masjid Kapitan Keling’.1 This thoroughfare is also dubbed ‘The Street of Harmony’,for several houses of worship representing a variety of world religions have co-existed here for over two hundred years, enriching the lives of denizens and visitors alike.

A Living Place of Worship

The Kapitan Kling Mosque is at the centre of a vibrant Tamil Muslim neighbourhood built on endowment land. The Tamil Muslims in this area assume a variety of occupations; they are jewellers, money changers, textile merchants, spice merchants, and food vendors. Families live in houses and apartments, buying their daily necessities and food from local shops and wet markets. Their children attend kindergarten at the back of the mosque. At the sound of the azan (Islamic call to prayer), Muslims from the surrounding shops converge on the mosque from all different directions. Many of the Indian Muslim shopkeepers here pray several times a day at the mosque, locking up shop for a lunch break and then dropping by the mosque again on their way home. There is also a steady trickle of tourists, travellers and itinerants who come to perform their prayers or to simply find a quiet place in the bustling city centre.

While open to all Muslims, the mosque has a strong Tamil character and heritage, dating back to the days when South Indian mariners and labourers were the backbone of the Penang port, manning the lighters and purveying European and Indian vessels. Indeed, the history of the mosque stretches back to the days when Tamil Muslims were called Chulias and the English East India Company – that sovereign-backed maritime multinational – ruled the waves.

The Kapitan Kling Mosque, endowment and community evolved for much of its history within the context of British colonial rule. Among Muslims of the South Asian continent, there is a fond regard for the number ‘786’, which is a numerical equivalent for the auspicious phrase ’bism illāh ir-raḥmān ir-raḥīm’.2 For Penang Indian Muslims, the number is doubly auspicious because the year 1786 (1+786) is the date when Penang was established as a British trading post. Penang became famous among the Tamil Muslims as a land of fortune, and it was from Penang that new networks of Tamil Muslim diasporas spread to the rest of Malaya and Southeast Asia in modern times.

Seller of sweatmeats, friend and children sitting on the front steps of a house. Wade Collection.

Place-making and Endowment

A local perspective can be adopted in charting the evolution of the Tamil Muslim community in Penang. Within this port town, the Kapitan Kling Mosque is the principal mosque and centrifugal institution which historically provided Muslims of Indian origin with a symbol of belonging and a sense of place, and continues to do so today. Rather than state or national boundaries, the port town or ‘port cluster’ (the locality where all services related to the business of the port are concentrated) is taken as an appropriate geographical scope for ‘pinning down’ this historical diaspora.

Like all historic cities, the George Town World Heritage Site illustrates layers of ‘place-making’; the latter is simply defined here as the act of making places meaningful. The colonial regime implemented ‘top-down’ processes of place-making – the sponsorship of new architecture, recreational spaces and civic amenities, and the creation of a public realm which offered residents and visitors the experience of ‘progress’, ‘prosperity’ and ‘modernity’. The various indigenous and Asian diaspora communities implemented ‘bottom-up’ processes of place-making through various processes of human settlement, architectural construction and landscape patterning, the creation of sacred spaces, the inscription of social memory through ritual performances, as well as enduring patterns of communal land use.37 Each diaspora made a home away from home by establishing a network of interconnected ‘transcultural spaces’ imbued with cultural-religious values reflecting their ethnic origin and affirming their diasporic identity.

The colonial administration gave official names to streets as one strategy for ordering the town. In George Town, South Indian Muslims lived and worked on Chulia Street (originally named Malabar Street). Kampung Kolam and Jalan Masjid were also named after Tamil Muslim places. Kampung Kaka, Kampung Malabar, and Dato’ Koya Road were the street names for Malabari settlements which no longer exist. Kampung Takia was an unofficial place name for a Tamil Muslim settlement; it made way for what is now Ah Quee Street.

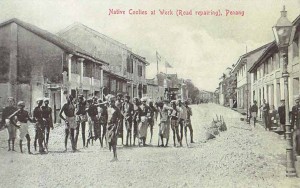

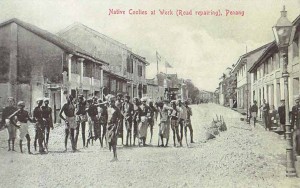

‘Native Coolies at Work (Road repairing), Penang’. A ‘chain-gang’ of labourers undertaking road repairs on Transfer Road, being watched by their overseers (right) from the colonial public works department. In the background is the Keramat Dato’ Koya, marked by a pair of flags. Wade Collection.

Imperial and vernacular place-naming often co-existed. The simultaneous use of English, Tamil, Chinese and Malay place names is evidence of historical layering of an urban space. Various communities gave their own place names to locations they used, which nurtured familiarity, recognition and attachment to their new temporary or permanent home. Both Muslim and Hindu Tamil speakers shared the same mental geography of the city and have common Tamil place names for streets, junctions and settlements, reflecting their economic activities. Weld Quay was known as Padahu Thurai (‘boat yard’). King Street was Padahukara Teru (‘boatmen’s street’), the street of Tamil boatmen, sailors and fishermen. Market Street was Kadai Teru (‘street of shops’). Penang Street, where the Nattukottai or Nagarathar Chettiars have their lodge and warehouse, was known as Kittingi Teru (‘street of Chettiar premises’). Green Hall was called Uppukaran Teru (‘salt traders’ street’) where salt was dried and stored in godowns. The junction of Pitt Street and Buckingham Street, in front of the Kapitan Kling Mosque, was called Yeela Muchanti (‘auctioneer’s junction’). The junction of Penang Road, Chulia Street and Argyll Road was named Rajati Medu (‘the Queen’s mount’) after a grand arch erected by the Kadayanallur community during an imperial celebration.38 The junction of Larut Road and Hutton Road was named Thanni Salai (‘water road’) after a tank which supplied water for sale. Many of these vernacular place names reflect the activities of the Tamils who were concentrated in the port area. By comparison, two very early Tamil Hindu villages are found in the outskirts: the washermen’s village at Dhoby Ghaut along the Pinang River and the doolie carriers’ village called Narkalikarar Thandal Kampam at Waterfall Road near the Moon Gate.39

In Penang as elsewhere, Muslim places of significance were often associated with waqf: an endowment, created according to the stipulations of Islamic law, to be held in perpetuity while its usufruct should be devoted to its religious or philanthropic objectives. Waqf has been an important institution in Tamil Muslim society, both in India and among the diaspora.40 Community patrons often dedicated waqf in response to community needs, thereby earning both social prestige and spiritual reward. Mosques and burial grounds were endowed for the use of the Muslim community, while Sufi saint-shrines (dargah) were important places of resort for both Muslims and Hindus, thus providing an integrative transcultural space. While endowments were but one process of place-making, they were often retained and inscribed in the social memory due to their religious and supposedly permanent nature. Even a piece of waqf property which had been wrongly sold or misappropriated would be remembered for generations later, although particular details might be disputed.

The port town, especially the area on both sides of Chulia Street, is dotted with evidence of Tamil Muslim endowments. Mosques and saint-shrines endowed by Tamil Muslims were built not only in town, but also in every suburban or rural settlement where there were substantial numbers of Tamil Muslims. Feasts (kenduri) were localized forms of patronage, as the richest in the society were expected to maintain regular benefactions towards their kinship groups and immediate community; though usually meagre and ephemeral, these benefits would be tangibly and emotionally felt by the poorest in the society. Festivals and procession routes helped expand the geography of the diaspora, allowing them to assert a stake in the urban space.

The Burmah Road mansion of Shaik Eusoff Gunny Maricar. He was a Penang harbour pilot, patron of the Nagore Dargah and president of the Muslim Society, Kapitan Kling Mosque. Courtesy of Alex Koenig.

Apart from the well-known Kapitan Kling Mosque and the Nagore Dargah, which continue to be frequented, many religious sites and domestic buildings associated with the Chulias are today found in an abandoned and derelict state. A few have been refurbished with little understanding of their cultural significance. Yet physical records point to the major historical importance of the South Indian community in the port area of Penang in the nineteenth century, a much more substantial presence than what is visible today. The Kelly map of 1893, which shows an array of built forms, brick bungalows, wooden cottages and warehouses, as well as more regular shophouses, also reveals an abundance of Muslim urban heritage – mosques, dargahs, mausoleums, burial grounds, even an Indian tank and an ashurkhanah, all of which will be elaborated upon later. Many private properties formerly belonging to wealthy Muslims have been sold off and demolished, but the institution of waqf (which implies the meaning ‘to retain’) has preserved some of this built heritage.

When faced with such enduring evidence, an urban historian can only ask, who were the Chulias? Why were they so important to early George Town? What happened to them? This book is an attempt to answer those questions and to add another layer of historical interpretation to the rich historic urban landscape of the George Town World Heritage Site.

A nineteenth-century view of Chulia Street, showing the street congested with bullock carts and rickshaws. The twin miniature minarets of the Nagore shrine can be seen. Wade Collection.

Organisation of the Book

The book is divided into six parts, each roughly corresponding to a historical period. Each part is divided into individual chapters which look at the dominant themes of that period. The construction of this social history depends greatly on English sources available to the author, supplemented by limited Malay sources as well as minimal Tamil sources.

Part One, entitled ‘A New Port for the Chulias’, depicts the maritime trade of the Chulias in ancient times and during the period leading up to the establishment of the British trading post of Penang in 1786. The new settlement was ruled from the Bengal Presidency, and was itself elevated into the Penang Presidency (1805–30). Significant milestones include the Siamese invasion of neighbouring Kedah in 1821 and the incorporation of Penang into the Straits Settlements in 1826.

Chapter 1, ‘Indian Ocean Connections’, provides a general background of Chulia traders in the East Indian Ocean and their competition and cooperation with European trading companies, then narrows its focus on the Chulias in the Straits of Malacca, and British dealings with Aceh and Kedah before 1786.

Chapter 2, ‘Early Settlers and Mosque’, looks at the Chulia population of early Penang – the traders, mariners and sepoys who took up land and trading opportunities in the new settlement. In order to encourage them to settle, the East India Company gifted land for a mosque and burial ground.

Chapter 3, ‘Piety and Patronage’, shows how the Chulias created their own centres of spiritual protection. Sufi saints had already left their mark on the precolonial spiritual landscape, which played a role in encouraging assimilation and conversion. The establishment of the Nagore Dargah strengthened the connection between the Nagore merchants and the new port of Penang.

Chapter 4, ‘The Kapitan Kling’, profiles Cauder Mohuddeen as a Marakkayar shipping merchant and community leader. It looks at his origins from Porto Novo and his role as ‘Captain of the Chulias’, in which capacity he took on leadership in mosque-building. Cauder Mohuddeen was made an example of by the courts as soon as the judicial system went through a transition from a pluralistic legal system to English law.

Chapter 5, ‘Munshis and Malay Writers’, features Long Fakir Kandu, a Chulia from Kedah, who was involved in a long-standing land dispute with Cauder Mohuddeen. His two sons, Ibrahim Kandu and Ahmad Rijaluddin Kandu, were Malay scribes who authored two significant works of pre-modern Malay literature.

Chapter 6, ‘Family and Legacy’, relates several accounts about the Marakkayar women who feature prominently in the clan history. Cauder Mohuddeen’s bequest, by which he created his familial endowment, is discussed in detail.

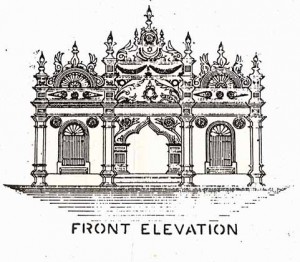

The Noordin family mausoleum on Chulia Street, Penang. ‘Proposed Wakoff Institution at Chulia St. for N. Morham’, plan submitted by E. Hogan, 1907.

Part Two, entitled ‘From Seafaring Merchants to Settlers’, dwells on the period after Penang’s demotion from its Presidency status in 1830. A few Chulias emerged as prominent merchants in Penang, and several chapters are devoted to these leading families and their legacies. This period is marked by several watersheds: the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the dissolution of the East India Company and the inauguration of the British Raj in India, as well as the subsequent transfer of the Straits Settlements from India to the Crown in 1867, all of which had repercussions in terms of British attitudes towards their Indian Muslim subjects.

Chapter 7, ‘Penang as a Centre of Marakkayar Trade’, looks at how, partly due to European control over other ports, Penang became the foremost port for the Chulias on this side of the Indian Ocean. The triangular trade between the Coromandel Coast, Penang and Aceh – shipping textiles to the Southeast Asian market in exchange for betel nut and pepper for the Coromandel market – was the mainstay of Penang Chulia businesses. The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 accelerated the domination of the seas by European steamships. The invasion of Aceh by the Dutch in 1873 destroyed the Muslim sea trade and spelt the end of the golden age of the Penang Marakkayars.

An old Indian property along Chulia Street with a large communal kitchen. SN Khoo.

Chapter 8, ‘The Jawi Peranakan’, samples descriptions made by a number of observers of this culturally hybrid community and examines various educational influences on this group.

Chapter 9, ‘Pepper and Pelikat Tycoons’, describes the patriarchs of several famous Jawi Peranakan families and their estates. The leading Chulia merchant Mahomed Noordin died in 1870 but his legacy remained considerably intact for another half a century.

Chapter 10, ‘Women with Status and Property’, gathers information about Marakkayar women of this period from wills and court cases.

Chapter 11, ‘Diversity, Difference and Division’, sketches a picture of the Indian society in nineteenth-century Penang, when the presence of military regiments and convicts added to its heterogeneity. During this period, social divisions manifested themselves in terms of competing religious authorities and popular participation in secret societies. This chapter also describes the Penang Riots of 1867 and the practice of alternating mosques.

Chapter 12, ‘Cultural Expressions’, uses the insights from previous chapters to offer some tentative new findings on the cultural phenomena of Awal Muharram, Boria and Bangsawan.

The ‘Empress Victoria Jawi Peranakkan Theatrical Company Penang Indra Bangsawan’ in full costume. Reproduced from Aruna Reena Singh, A Journey through Singapore: Travellers’ Impressions of a By-Gone Time, 1995.

Part Three, entitled ‘Mosque, Endowments and Community’, discusses the circumstances and consequences of government decisions affecting Muslim endowment lands: firstly, as a result of various court judgements, secondly, by way of fervent implementation of the Municipal Ordinance of 1887, and thirdly, through the legislation of an ordinance in 1905 governing ‘Mohammedan and Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments’. By the end of the nineteenth century, the term ‘Chulia’ had been largely replaced by the term ‘Kling’: therefore, except where the latter word appears in quotes, the contemporary term ‘Tamil’ or ‘Tamil Muslim’ is used in this book to refer to Muslims originating from Tamil Nadu, providing a clearer identification of the people mentioned.

Chapter 13, ‘Religious Endowments’, discusses the making of endowments by Muslim testators, and their unmaking by the British courts. The elaboration of the concept of waqf and its significance in the Penang context lays the foundation for the rest of Part 3.

Chapter 14, ‘Land and Leadership in Dispute’, profiles Pa’wan Abdul Kader, the pilgrim agent, and the other grandsons of Cauder Mohuddeen. It chronicles the disputes between them in relation to the management of mosque lands and the Cauder Mohuddeen family endowment.

Chapter 15, ‘Reforming Muslim Endowments’, provides background information on the establishment of a government-appointed Commission to inquire into Muslim endowments.

Chapter 16, ‘The Consultative Process’, follows two lively debates that took place among the Muslim community in 1904: firstly, the likely benefits of proposed government reforms to Muslim endowments, and secondly, the election of a new qadi. Hadhrami Arab personalities assume positions and influence the outcomes.

Chapter 17, ‘The Endowments Board’, explains the setting up of the Mohammedan and Hindu Endowments Board and the powers and functions exercised by the Board.

Chapter 18, ‘Urban Transformation’, describes the dramatic changes to the environs of the Kapitan Kling Mosque, propelled by the new Endowments Board.

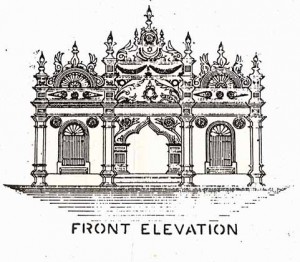

Chapter 19, ‘Reimagining Mosque Architecture’, traces the architectural development of the Kapitan Kling Mosque from its first known form (c. 1801) to the last major pre-war expansion (c. 1925).

The Kapitan Kling Mosque and minaret in polychrome Indo-Saracenic style, as it was designed by the architect H.A. Neubronner. Courtesy of Chua Hock Khoon.

Part Four, entitled ‘Social Movements and Modernity’, gives an idea of the competing worldviews of the early twentieth century, shaped by the print media, and their impacts on the Penang Muslim community. Trends in religious reform and secular modernity, pan-Islamism and British Empire loyalism, the Self-Respect Movement and Malay ethnic nationalism are traced. To illuminate these complex topics, the section follows the careers of a few historical personalities associated with the Kapitan Kling Mosque, the commercial town and the port milieu, each representing certain visions, aspirations and agendas.

Chapter 20, ‘The Press and Pan-Islamism’, gives prominence to the pioneers of the Tamil press and Malay press based in Penang at the turn of the twentieth century, and highlights reports on the Tamil Muslim community’s participation in imperial celebrations as subjects of both the British Empire and the Ottoman Caliphate.

Chapter 21, ‘The Mohammedan Advisory Board’, discusses the repercussions of the Singapore Mutiny of 1915 and the colonial government’s increased monitoring of Muslim affairs. The Board’s establishment inaugurates a new relationship between the colonial state and its Muslim subjects, acted out through symbolic events such as the opening of the Kapitan Kling Mosque minaret.

Chapter 22, ‘Religious Reformists and Rifts’, describes Malay views of ‘Tamil Islam’, and the tensions between ‘Islamic modernists’ and ‘traditionalists’ which were heightened when Penang became a centre for Muslim intellectuals and educationists.

Chapter 23, ‘Social Leadership’, relates the migration of the Kadayanallur and Tenkasi community to Penang, and profiles the leadership of the Muslim Merchants Society and the Muslim Mahajana Sabha. It looks at how Penang Tamil Muslims responded to First World War taxation, the Khilafat Movement of the early 1920s, and issues arising from the trafficking of Indian labour to Malayan plantations.

Chapter 24, ‘Diverging Identities’, describes the dynamics fostered by various modern associations: the character-forming Mohammedan Football Association, the self-positioning Penang Malay Association and the grassroots-affirming ‘Dravidian resurgence’ of the Self-Respect Movement. The future direction for identity politics is set by the call for ‘Malaya for the Malays’ on the one hand, and the separatist agenda of the All-India Muslim League on the other.

The Muslim Mahajana Sabha, gathered to celebrate Hari Raya. Its president, P.K. Shakkarai Rawther, with white moustache and beard, is seated at front centre. Courtesy of Yusoff Azmi Merican.

Part Five, entitled ‘The Port Cluster’, is a preliminary study of Tamil businesses and occupations within the port sector as well as the service sector that supports it.

Chapter 25, ‘Business Networks’, notes the expansion of Tamil Muslim retail networks, lists some of the traditional trades and occupational specializations of the Tamil Muslims in the port town, and features a business trademark issue which was taken up to the Privy Council.

Chapter 26, ‘The Penang Port’, depicts the general functioning of the Penang waterfront, examines the various niche areas of Tamil Muslim specialization and explains how this sector was adversely affected by neglected infrastructure and industrial strife.

Part Six, entitled ‘War and Politics’, serves as a sort of epilogue. It offers a cursory history of the Japanese Occupation and the immediate post-war years leading up to Malayan independence. While much more information about this period is still ‘out there’ waiting to be documented, a more comprehensive social history of Tamil Muslims during the war and post-war period would be beyond the scope of this book.

Chapter 27, ‘The Japanese Occupation’, draws on the eyewitness account of Captain Baba Ahmed, and focuses on the impact of the Japanese invasion and occupation on the Kapitan Kling Mosque and its qariah.

Chapter 28, ‘Post-War Politics’, looks at a period in which Indian independence and Malayan politics raise new issues of citizenship, loyalty and identity. Through the local branch of the Muslim League, Tamil Muslims in Penang engage in city and settlement politics. The book ends in 1957, the year George Town achieves city status and Malaya becomes an independent nation.

‘A Street Stall, Penang’ shows customers enjoying Mamak food at a street junction. Nasi kandar, gandum and other ‘mamak’ food used to be sold by itinerant hawkers carrying their food in baskets suspended from shoulder yokes (kandar). Wade Collection.

Vote for the book

The Chulia in Penang is also up for the ICAS Book Prize 2015 Colleagues’ Choice Award.